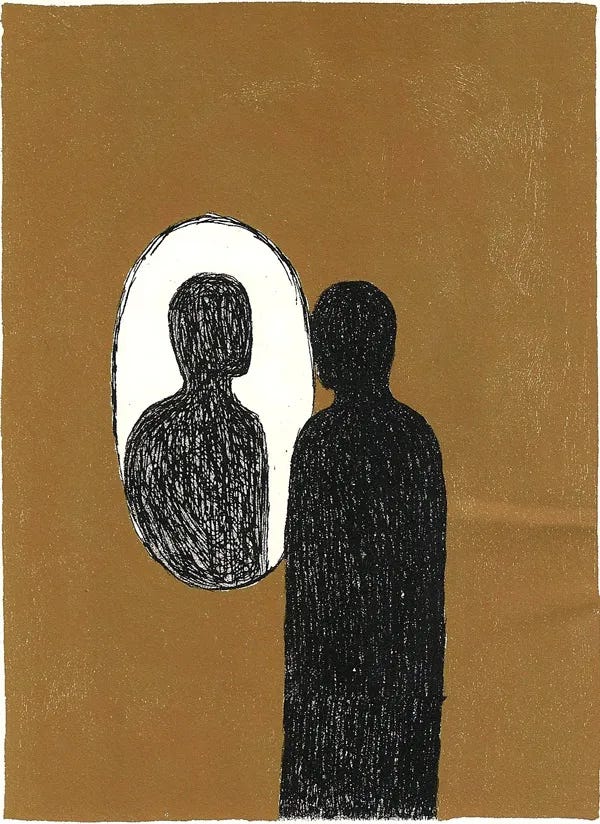

If there’s one thing a person devoted to an artistic profession wants to do above all else, it’s to define an identity. We must find a voice—that certain je ne sais quoi that makes us say, "this is me." In another post, I’ll delve specifically into what we call style, but first, I want to explore this question: What word defines us? I believe in the power of words and the weight of their meanings, so tackling this seemingly simple task is, in reality, a complex endeavor.

The Sketch

Between the ages of 10 and 12, I was one of the highlights of my class. Not because I was "popular," but because everyone wanted to read my comics.

I drew constantly at home, creating a wide array of characters for myself, but at some point, I thought it’d be a good idea to craft an action-adventure story featuring fictionalized (and superheroic) versions of my classmates. A year or two later, wanting to reflect the early adolescence I was living, I decided to draw a comic where all my classmates appeared in a rom-com style. These were strips full of entanglements, romantic relationships, and above all, humor. Like a pencil with a worn-down tip, the word dibujante (drawer/cartoonist) was sketched onto me—the term my classmates used to define me and what they assumed would be my future career.

Borrando con el codo

Yet life had other plans. By 18, I learned I couldn’t make a living from drawing, so I had to pursue a "serious" career and a "serious" office job. Drawing was tied to childhood—something frowned upon in the adult world. Though I tried to hide it, deep down, one idea was etched in bold: I wanted to be a comic book artist. Both dibujante and historietista (comic artist) filled me with warmth, a closeness to that future audience of my pages. I treasured those words, knowing what they meant to me.

About five years later, with a "serious" job and a "serious" degree, I thought I was on the right adult path. Of course, I wasn’t—because the screams of my artistic side were deafening me. Unlimited internet access introduced me to a new world: people who could live off their drawings. But they no longer called them drawings—they called them art. And they weren’t dibujantes or historietistas; they were artists.

At the time (and even now, a little), the word art felt distant to me. I always associated it with high society—a world I didn’t belong to—with European paintings I didn’t understand, and artistic movements I knew nothing about. But borrowing those terms lent a certain prestige to the craft of drawing; they sounded more "adult" and less tied to childhood. I didn’t yet define myself that way, but I assumed those were the "right" words to adopt.

Outlining the Edges

In recent years, I’ve ended up adopting and defining myself as an artist in various corners of the web. Partly because it felt like a term that encompassed the many facets of my interests, and partly because many international comic creators use it to introduce themselves.

I also define myself as an illustrator—a word that carries the prestige of artist while specifically pointing to the craft of drawing. Both artist and illustrator are cognates, so beyond their meanings, they’re convenient for readers of other languages.

These terms are applied like a fine-tipped brush—delicate, but unable to unleash the full force of the stroke. And though I like fine brushes, I’ve never felt entirely at ease with them.

Details and textures

Over the last few years, I’ve refined my knowledge of drawing, artistic movements, tools, and more, while also roughly sketching my worldview. I reflect on the structures we borrow from other countries, the unique needs of this craft in our local context, and a possible future to draft within our circumstances. I want to move away from pompous or romanticized notions of this work—I want to connect with people. I want to embrace the rawness of a broken pencil, the struggle of finding textured paper. I want to express myself as authentically as possible. And I remembered that word I once treasured, now ripe for redefinition. Being a dibujante is an affirmation of my principles.

Francisco Solano López was the person that made Hector Oesterheld's writings come to life in El Eternauta, the most influential comic book (and not a graphic novel) in Argentina. Do you know how does Wikipedia define him? As a dibujante.

The final draft

When I began taking this drawing path more seriously, I set a clear goal: I want to bring my stories to the world. I want to tell them and be read—to hear what people liked, what they didn’t, and what made them think. And though the immediacy of the internet suggests closeness to an audience, it often feels like shouting into a muted megaphone.

I cherish the intimacy of a relationship with future readers. Few things bring me more joy than someone telling me they love my work or are eager to see what I’ll create next. Defining myself as a dibujante brings me closer to that warmth I seek to create—and which, in turn, transforms me through others.

In a world where everything is volatile, where words are swept away by an upward scroll and social media feels more algorithmic than social, I want to carve out a space that fuels my creative drive. Just like when a circle would form around my desk at age 10 whenever I brought a new comic, I want that genuine back-and-forth warmth with my audience. With a pencil in hand, all that’s left is to keep drawing my path. That’s what sketches are for: to keep tracing lines.